Dafydd Davis is a man who will always be overshadowed by his creations. Responsible for kick-starting the entire trail centre concept in the UK, beginning with Coed-y-Brenin in Snowdonia, it’s not overstretching a point to say that without him there would be no Glentress or 7Stanes, and certainly no Afan or Cwmcarn. So that’s no White’s Level at Afan and no mbr trail at Coed-y-Brenin… it’s a frightening prospect.

Perhaps the trail centre revolution Dafydd started back in the 1990s would just be getting rolling now, a trail-builder taking the first tentative steps: approaching the Forestry Commission with the seminal idea, and being rebuffed by a wall of apathy.

Because that’s exactly what happened to Dafydd. While the Forestry is firmly behind the trail centre concept these days — and has been for many years now — it wasn’t always like that. Initially employed by the Forestry Commission as a recreation ranger, Dafydd began his career as an unofficial trail-builder by “ducking and digging trails” as he puts it, in the stunningly beautiful Coed-y-Brenin forest, with “absolutely no support” for building them. It was a struggle many years in the making to get the Forestry to see the wood for the trees.

So that’s where I’ve come on a crisp autumn day, back to where it all began, to tell the story of the trail centre and its future. Driving to meet Dafydd, it strikes me just how unsuitable Coed-y-Brenin was for the first ever centre. Not because the natural environment isn’t right — Snowdonia obviously has more than enough elevation and gradients, and it’s a stunning place to be — but because it’s just so remote. It may only be 100 or so miles from Birmingham, but that represents a good two-and-a-half hours in the car. It’s a tiring drive too, constantly shifting up and down the gears, either on the brakes or the accelerator as you snake through the mountains. And in winter it can be downright dangerous — last winter the snows made some of the roads impassable for weeks.

Perfect day

The weather is perfect today, but I’m already exhausted when I meet Dafydd in the visitor centre cafe, while he’s fresh and chipper after a short drive from his home near Blaenau Ffestiniog. He says he wouldn’t leave the place for a “100 grand a year down in London”, staying instead for the love of the land and the outdoor lifestyle. He’s dressed not for riding, but for walking — or possibly ice climbing — with big-brand outdoor gear festooning his frame and serious walking boots on his feet. I’m hoping he has something to change into.

We’re not riding that far though. Dafydd has a ruptured disc in his back and doctors have advised him to stay off the bike. They’re made of stern stuff up here though, and he’s going to ride some sections to give us a flavour of his loop, and link it up for us by driving in-between.

It’s a loop comprising part natural big-mountain riding, part old-school rocky singletrack and part newly crafted trail. Think of it as a journey through the life of UK mountain biking in four hours, taking in something old, something new, something borrowed from the natural landscape and something blue graded. “Take a packed lunch and a flask of tea and maybe a hip flask and some cigars,” Dafydd quips, a clipped English accent replacing the Welsh sing-song for a moment. “And one of those big check rugs.”

For starters

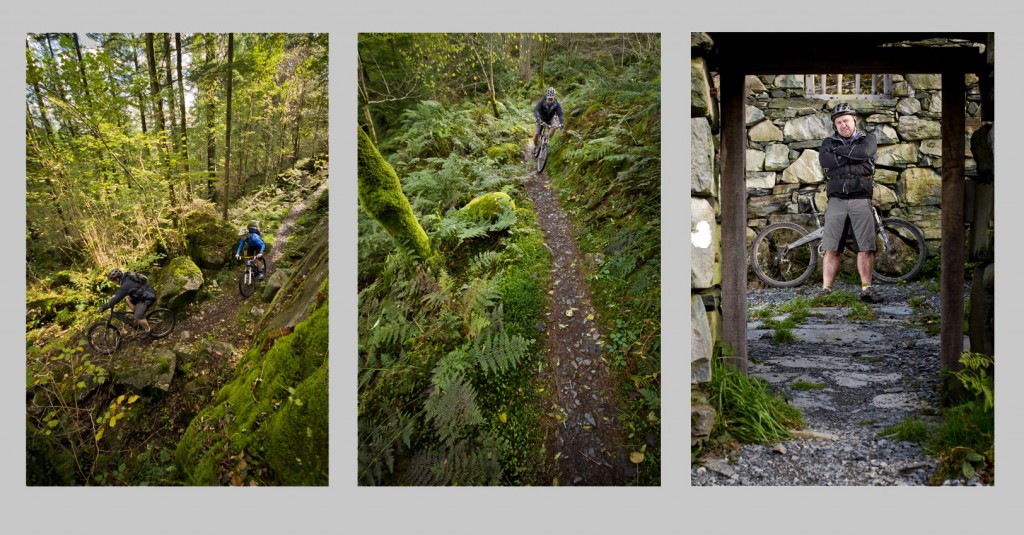

Appropriately then, we begin at the beginning, on one of the oldest sections of trail: the Flightpath. Dafydd has now pulled on some proper riding gear and unhitched an ancient, uncared-for Orange Patriot from his car. I hop on for a quick spin, before realising the rebound on the shock is useless and the whole thing feels like a pogo stick. Perfect for rock hopping.

Flightpath is a piece of trail that means a lot to Dafydd: it’s rocky as hell, with massive boulders leaning in from either side and vegetation crowding round. “It was a huge effort to build,” Dafydd remembers with pride. “From myself and also from the RAF labour we used. It was all built by hand and pretty much all of it is stone pitched. We moved some massive rocks around in there.”

It’s also incredibly natural-looking, and fits just perfectly with the landscape, as if it had always been a trail. “I’m just really pleased the way it sits there,” he says. “Sometimes people think that’s accidental but it’s not — I was trying to show mtb’ing could be a legitimate countryside activity because we could do it in a low-impact way.”

Flightpath is typical of Coed-y-Brenin and the original style of trail built in the Nineties by Dafydd — rough and untamed, and certainly low impact, sitting quietly in the forest. Dafydd is naturally defensive when I bring up the criticism that his trails lack the flow and speed we’re used to on modern trails. “We didn’t have any money,” he explains. “Essentially we used what we had there. We didn’t import material to the same extent trail-builders do now.” He’s also a realist — smooth and fast trails need more money for maintenance and to keep them smooth and fast, while rocky trails take care of themselves.

It’s a testament to Dafydd’s perseverance that anything was built at all here. “I was operating at a level way above my pay grade,” he says. “But I had to, as at the time there was no support at all within the structure of the Forestry Commission for what I was doing. I was trying to persuade people that strategic trail-building was a good idea, and why it was a good idea.”

Talking money

The good bit, of course, is money. Lots of it. Coed-y-Brenin wasn’t given the green light because it would get more people into riding or because it would give more great trails to the UK, but because it would draw money into an area starved of investment. It would regenerate businesses and provide employment for local people and rebuild the social scene. On the back of the success here, it’s a model that’s been taken up by local politicians, land management organisations and councils across the country to boost tourism. Dafydd remembers a great conversation he had at the time with a local woman fed up with the sight of blokes in luminous pink and yellow Lycra (admit it, you remember the style) wobbling around on mountain bikes: “‘What have mountain bikers ever done for us?’ she said. ‘They are a nuisance, so many of them wear bright colours’. Turns out, her daughter worked in the pub where 90 per cent of the clientele were mountain bikers.”

Eventually, a measly few thousands were granted for trail-building at Coed-y-Brenin and a few kilometres of singletrack were painstakingly hewn. Build it and they will come, Dafydd hoped, and his belief paid off.

“The visitor centre went from being on the verge of closing,” he says. After those initial trails were put in, Dafydd was able to conduct surveys to discover why people were visiting the area and even put counting equipment onto the trails, the car parks and the cafes to get an accurate idea of visitor numbers. Numbers of visitors had grown from tens of thousands to around 150,000.

“That really was what lit the blue touch paper,” he says. “Politicians went: ‘wow, this is mental’. At that time, nobody had really measured the impact of outdoor recreation on the countryside, and that didn’t happen until after foot-and-mouth. Then people started to think about the impact foot-and-mouth had on the general economy, beyond agriculture. It didn’t take a genius to figure it out that people go to the country to do more than just drive around little lanes and have picnics; they want to do stuff. That was the real change. The reason people were travelling such a long way to be here was because of singletrack trails — which at the time in the UK were very much at a premium. They knew the kind of riding they were going to get so it was worth travelling to, and it was waymarked — they didn’t need to get a map out and find their way. They didn’t need to keep getting off their bikes, opening gates or getting over stiles. So I could say to the Forestry: people like this model, they like it because of those details.”

Part of the ride Dafydd has mapped out for today does involve opening gates and clambering stiles however, so we pile into his battered 4×4 to get a flavour of it. The smell in the car is something like a ripe brie — thanks to a winter and a summer’s worth of soggy wetsuits and climbing gear stashed in the back — so I’m happy when we reach our destination, and pile out and back into the fresh mountain air. I suck it in and life returns to my nose and my eyes stop streaming.

There’s a good reason for taking riders up here though, through the Bwlch Goriwared pass (meaning back-to-front pass) and high above the forest: “It’s a different perspective on the area, Dafydd says. “You get this real feeling, you get to see where Coed-y-Brenin is in relation to the rest of the landscape. I think it’s a great section.

“What are trails all about, after all? They’re about getting connected to a landscape, to a place, whether you’re going for a walk or throwing it around the place on a bike. Whether you’re on a bloody bike with stabilisers or a downhill bike: in some way you are connecting to that landscape and the best trails are the ones that reflect that terrain and are sympathetic to it.”

The view is spectacular from the top of the pass, outrageous even, he says, looking out right across Coed-y-Brenin. “Across at the Ffestiniog Mountains to the left, and you can see Snowdon straight in front of you. It’s spectacular and wonderful. I used to ride over there all the time, before we built the trails. I learnt a lot from looking at natural trails, and digging holes in them; how it was built and what it looked like.”

Back in time

If you really want to find the beginnings of the trail centre revolution, you have to go to a 19th-century country retreat in the Vale of Ffestiniog, to an old manor house called Plas Tan y Bwlch. The trails here are 130 years old, possibly the best Victorian footpaths never to see plus-fours or a penny-farthing.

“It’s used a hell of a lot and there’s nothing wrong with it, but it’s so lovely and it sits in the landscape so well — I took a lot of my inspiration from that. They were built for the ladies of the manor to go for a walk on, or take a pony along. Technically it’s illegal to ride a bike on it but lots of people do. There’s never any maintenance done but they look and they feel very natural — you would never guess that they were actually built.”

We’re losing the light now on our Killer Loop, so it’s time to get down off the high mountain and head to one of the newly built sections that Coed-y-Brenin has recently had developed. It’s years since Dafydd rode at the trail centre thanks to his dodgy back, and even more years still since he worked for the Forestry Commission, so this is the first time he’s sampled any of the new sections here.

We ride onto the new blue trail, designed to bring beginners and families into the sport, and of course to promote tourism in the same way the original Nineties red trails did. We come to a stop at the top of a series of berms and tabletops carving their way down the hill in front of us. The trees have been felled in a 50ft-wide swathe to make way for this trail, and a wide stretch of grey asphalt points the way downhill. As we watch, a lady with a baguette in the basket of her touring bike screeches her way round a berm and nearly goes over the bars on the tabletop, before another rider with a dog in tow brakes his way round.

“They’re going to have a lot of problems here,” Dafydd says grimly.

He’s not impressed with this new trail. “I think it’s inappropriate, when you look at how beautiful Coed-y-Brenin is. It’s not a manicured place, it’s a landscape with a wild feel to it.

“It’s had an awful lot of impact on the forest itself, those berms. There’s nothing wrong with wide, flowy berms with tabletops on… in the right places. I’m just not convinced that’s the right place.”

The trail is in stark contrast to the natural pass we just left and the original red routes Dafydd designed that have grown into the landscape — there will be no ignoring this new trail.

“What people shouldn’t forget is, Coed-y-Brenin is a really important landscape that’s highly valued by a lot of people, not just mountain bikers. There’s been a forest there since the 11th century. It’s a heritage landscape in a national park and it’s a beautiful place.

“I worked really, really hard to make sure the trails I put in there sat in the landscape, didn’t impact negatively and didn’t devalue it for people who weren’t mountain bikers. I’m just a bit uncomfortable with doing that kind of trail in a public space, like Coed-y-Brenin, that’s of such importance. In some quarry, in private land or some crappy plantation in the middle of nowhere that’s fair enough. But Coed-y-Brenin is a wee bit too important in landscape terms.”

He’s really animated now, much more so than when describing his past achievements, or going over the story of how the beginnings of the trail centre. This is clearly a place he still loves.

“They’re doing it this way because it’s cheaper. It’s easier than putting trails around the trees and with a lower impact. It’s much easier to do it in a heavy-duty way.”

It’s an approach that would not be accepted by other countries, Dafydd says. He’s recently been working with the Department of Environment and Conservation in Perth, helping them implement a strategy for trails in Western Australia. They wouldn’t even consider this ‘high-impact’ approach, he explains.

“The people [in Australia] are custodians of the landscape, of the environment. You look at the way the Forestry has been doing stuff in the last few years in Coed-y-Brenin and I think it betrays the fact it’s being done by people with a background in forestry and civil engineering and not a background in design or countryside management.”

If this sounds like an attack on the Forest Commission and the creation of new trails, it’s not meant as such, says Dafydd. And this is from a man who has “nothing to fear” from speaking his mind on the subject — no need for more work from the Forestry (he runs his own trail-building company now, www.trailswales.co.uk), no fear of reprimand, just a general love of the landscape.

“It’s great if we get more trails — it brings more benefits to the community. That’s a brilliant thing. But with a big impact on the landscape? It’s so constrained and it’s under so much threat.”

What needs to happen is a discussion about trail-building, where it goes from here, he says.

“I feel very isolated — I sometimes feel as if I’m the only person saying this stuff. You would think IMBA (the International Mountain Biking Association) would be championing more sustainable trail development, landscaping and diversity. But it doesn’t do that at all.

“If we end up with trails done in this highly manicured, engineered way, high impact on the landscape and environment, mountain bike trails will only be built in certain places. And all we will have is the same model, cookie-cuttered out all over the place — and I don’t think that’s going to be good for anyone. There needs to be more of a constructive, informed and intelligent discussion about this. Do we really want the same kind of trails everywhere?”

I’m not sure I do want the same kind of trails everywhere, springing up like Costa coffee franchises, and I’m very sure Dafydd doesn’t want them. It’s also quite likely those of us who read the frenzied outpourings in this esteemed magazine also don’t want the same ‘cookie-cutter’ approach. More trails, yes, more identikit trails, no. But local councils and politicians do want them because they are a potentially large source of revenue from tourism. The thinking behind it is simple — there are millions of ‘mountain bikes’ in the UK, so why not build beginner trails for them?

Future down under

Dafydd’s future lies in Australia, at least in terms of work. Our ride is over as he has to fly to Perth tomorrow for “meetings, lots of presentations, lots of croissants and Danish pastries”. He’s also there to help develop their trail strategy, putting sustainable trails into the forests near major population centres. And before he goes he has an appointment with an osteopath (presumably to prepare his back for the torture of 24 hours in cattle class) — “they’re like gold dust around here,” he says.

Dafydd Davis still lives in the shadow of the forest he helped sculpt. As he drives off I’m left wondering whether returning to Coed-y-Brenin and riding again after so many years hasn’t been an emotional experience for him: pleasing to revisit the trails he dedicated half his working life to, and at the same time sad in the changing face of the forest. Perhaps even sadder that he’s no longer involved.